The Bill of Rights and Constitutional Interpretation

January 25th, 2013

By Dan Miller

Part III

Part I dealt with guns and the Second Amendment. Part II dealt mainly with the First Amendment. This Part III looks at the origins and purposes of the Bill of Rights and questions the direction in which our nation is headed.

The Bill of Rights in general

When the Constitution was being considered there was opposition to inclusion of any Bill of Rights and the Bill of Rights as we now know it — the First through Tenth Amendments — was added not long after the Constitution had been adopted.

The Founders’ indifference toward a bill of rights in the national Constitution was premised on the idea that it would not be practically useful. The experience of the states in the 1780s demonstrated that bills of rights, though suitable for theoretical treatises, imposed no effective restraints on those who would be responsible for protecting rights in practice. As Alexander Hamilton wrote in Federalist 84, the provisions of the various state bills of rights “would sound much better in a treatise of ethics than in a constitution of government.” Benjamin Rush similarly stated that those states which had tried to secure their liberties with a bill of rights had “encumbered their constitutions with that idle and superfluous instrument.” The Founders at the Convention believed that a bill of rights would be merely another “parchment barrier” incapable of restraining those who would seek to violate its provisions, and thus it would fail to provide true security for liberty. (Emphasis added,)

“Mere parchment barrier” is a good phrase and we should keep it in mind, particularly but not exclusively with reference to the Second Amendment. Unfortunately but with substantial justification, the Constitution as a whole seems to have become, or at least to be on the way to becoming, a porous “parchment barrier.”

There was also concern that since not all rights of the people could be encompassed within a Bill of Rights, adopting such a bill might imply that only the rights expressly mentioned in it were intended to be retained by the people.

To suggest, for example, that the liberty of the press is not to be infringed upon might imply that, without such a provision, the federal government would possess that power. The Founders feared that we might infer that they created a government with unlimited power and that the specific provisions in the Bill of Rights denote particular reservations of power from an otherwise unlimited government. (Emphasis added.)

In view of the ways in which the original Constitution (i.e., sans the Amendments) — the Commerce Clause of Article I, Section 8 for example — has been interpreted, those fears seem prescient, see below on New Deal legislation and its interpretations. Unfortunately, the various amendments did little to temper interpretations toward increasing power for the Federal Government and therefore less for the people.

The Ninth Amendment addresses such concerns as follows:

The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.

The Tenth Amendment importantly provides,

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people. (Emphasis added.)

In drafting what became the first ten amendments, James Madison

pointed back to the Declaration of Independence as the philosophic statement of rights and first principles; the amendments were not intended to replace or revise what had been set forth in that document. Therefore, the amendments should not be construed as enlarging the grant of power to the federal government by the Constitution, nor could they be thought to serve as a sufficient definition of all the rights and privileges of citizens. (Emphasis added.)

These points illustrate the crucial importance of the Ninth and Tenth Amendments. Those amendments were drafted and ratified to prevent the Constitution from becoming a carte blanche of authority to an unlimited government. Neglect of these amendments by the public as well as the courts has been so conspicuous as to illustrate the force of the Federalists’ original objections to a bill of rights. Yet for Madison, these amendments were central. They were intended to prevent the false interpretations that might be placed upon the provisions enumerating powers in the Constitution. (Emphasis added.)

The Declaration of Independence was not self-executing and neither is the Bill of Rights. Nor is it dependent upon governments alone to guarantee or to respect it; indeed, governments are the only possible culprits in violating not only the Bill of Rights but the rest of the Constitution. The Constitution authorizes the Federal Government to do various things and only those things. The Bill of Rights attempted to guarantee that the Federal Government would not exceed the authority granted to it and specified some but not all of the rights of the people that the Government can may not violate. The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments generally extended the prohibition against Federal violation of the rights of the people to the States as well. No person, acting solely in his private capacity, can violate the Constitution; private citizens have only the ability to violate laws promulgated in alleged conformity to it.

The safeguard of individual liberty, Madison reasoned, must lie with the people themselves. It is the people who must be responsible for defending their liberties. And a bill of rights, Madison and his colleagues finally concluded, might support public understanding and knowledge of individual liberty that would assist citizens in the task of defending their liberties. (Emphasis added.)

The Honorable Justices of the Supreme Court. The times they are a changin’.

If the people are unable to defend their liberties, who is likely to do it for them? The Legislature or the Executive Branch? I wouldn’t count on it. The Courts, maybe, but only if requested by someone directly affected by a particular loss of liberty or property who therefore has the requisite standing. In addition, prosecuting or defending a case up to and through the Supreme Court is costly and can take years.

A bill of rights, they saw, could serve the noble purpose of public education and edification. As Madison confided to Jefferson, “The political truths declared in that solemn manner acquire by degrees the character of fundamental maxims of free Government, and as they become incorporated with the national sentiment, counteract the impulses of interest and passion.” (Emphasis added.)

Where has that national sentiment gone? Has it “gone with the wind?” Will it ever return?

Does the possession and use of firearms, as guaranteed by the Second Amendment, no longer rank among the possible methods (and one hopes last resort) by which “the people who must be responsible for defending their liberties” may do so? That is a legitimate concern and Part I attempts to deal with it. Without the rights guaranteed by the Second Amendment, we would appear to be left with little more than what the founders referred to as “parchment barriers.” That was not the intention and would be contrary to it. However, it may be well on the way to becoming the practice.

Where do these principles mean?

I submit that they mean the following.

1. The rights guaranteed by the Bill of Rights are pre-existing. They can be withdrawn only by subsequent amendment of the Constitution pursuant to Article V (see Part II of this series). Neither legislative action, nor bureaucratic action pursuant to broadly granted discretionary powers, nor judicial fiat can be permitted to impair those rights. Sometimes it happens anyway. Have we only a porous “parchment barrier?”

2. Other rights not expressly stated in the Constitution can properly be inferred from what it meant when adopted or amended. They can not be based on what popular sentiment may now or hereafter suggest should be granted. Nor can they be inferred from the Constitution if inconsistent with its specific or implied provisions that have not been amended pursuant to Article V.

3. Rights that are neither expressly stated in the Constitution nor properly inferred from it can be granted legitimately by statute, but only if rights expressly stated in the Constitution or properly inferred from it are not thereby infringed. This suggests that in most cases the rights that can properly be granted by statute are against only the Government, thereby limiting its own constitutionally granted prerogatives. Government has no authority other than as granted by the Constitution and it can presumably waive that. Rights against the Government legitimately granted only by statute can thereafter be abrogated by subsequent statute. The rights of the people, however, are extensive. They are pre-existing and no mere statute can legitimately waive any of them.

4. Statutory grants of rights, as indicated in #3 above, that infringe upon the constitutional rights of the people can be permitted only following the adoption of amendments to the Constitution pursuant to Article V. (See Part II.)

Popular opinions on the proper functions of State and Federal governments have changed over the years. Through various amendments pursuant to Article V, the Constitution itself has changed responsively. Unfortunately, it has also changed in response to popular sentiment, as reflected in statutes and in judicial interpretations, in disregard of the exclusivity of Article V.

Judges are not, and should not act as though they were, legislators. The consequences of judicial “activism” of that sort have commonly been unfortunate breaches of the “parchment barrier.” For example, many New Deal era and later interpretations of the Commerce Clause of Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution have distended it beyond recognition, certainly by its authors and by those who approved its adoption. The results of that distention have usually been to increase governmental power, at the expense of the freedoms of the people. Some of those interpretations followed FDR’s threats to “pack” the Court. Ultimately, he found it unnecessary to do that.

The legislation was unveiled on February 5, 1937 and was the subject, on March 9, 1937, of one of Roosevelt’s Fireside chats. Shortly after the radio address, on March 29, the Supreme Court published its opinion upholding a Washington state minimum wage law in West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish by a 5–4 ruling, after Associate Justice Owen Roberts had joined with the wing of the bench more sympathetic to the New Deal. Since Roberts had previously ruled against most New Deal legislation, his perceived about-face was widely interpreted by contemporaries as an effort to maintain the Court’s judicial independence by alleviating the political pressure to create a court more friendly to the New Deal. His move came to be known as “the switch in time that saved nine.” However, since Roberts’s decision and vote in the Parrish case predated the introduction of the 1937 bill, this interpretation has been called into question.

Roosevelt’s initiative ultimately failed due to adverse public opinion, the retirement of one Supreme Court Justice, and the unexpected and sudden death of the legislation’s U.S. Senate champion: Senate Majority Leader Joseph T. Robinson. It exposed the limits of Roosevelt’s abilities to push forward legislation through direct public appeal and, in contrast to the tenor of his public presentations of his first-term, was seen as political maneuvering. Although circumstances ultimately allowed Roosevelt to prevail in establishing a majority on the court friendly to his New Deal agenda, some scholars have concluded that the President’s victory was a pyrrhic one.

Since the courts normally construe the Constitution in light of precedent, their own or that of higher courts, the locomotive of constitutional abrogation — rolling along tracks of convenient interpretation — continues to run along those same tracks while gaining momentum as it has for many years. I am concerned that changes in the composition of the Supreme Court and of inferior courts during President Obama’s second term in office are likely to add more fuel to the firebox beneath the locomotive’s boiler and bring even more of that. When will we learn the rest of the story? Before or after it has become too late to do anything about it?

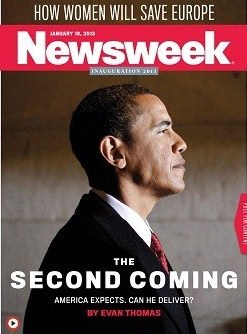

I was not happy with his “first coming” and expect the consequences of his second to be far worse. Will we soon arrive at the point where because “the people” want something and “the Government can” provide it, it will?

Not if the people think about it, but that is a gigantic “if.”

In that video, Mr. Whittle seems more optimistic than I am. I hope that he is right and that I am wrong. However, this slightly newer video suggests that his frustration, if not his pessimism, may be rising as his optimism wanes. Mine too.

(This article was also posted at Dan Miller’s Blog.)

Articles written by Dan Miller

Tags: amendment, Constitution, federal, judiciary, liberty, precedent, rights, state

Categories: Law, Politics | Comments (5) | Home

5 Responses to “The Bill of Rights and Constitutional Interpretation”

Leave a Comment

(To avoid spam, comments with three or more links will be held for moderation and approval.)

Authors

Recent Posts

- Opinion Forum Is No Longer Posting New Articles

- Government Needs to Get Bigger. Quickly.

- Cognitive Biases Are Bad for Business

- Hail to the Chief! Of What?

- Obama and Islamists Unite to End Abuse of Women

- David Axelrod Is Right: Government Is Too Big and Uncontrollable

- Does Modern Academia Encourage Unthinking Acceptance of Authority?

- The White House Did NOT Change Any Benghazi Talking Points!

- Trust – but Verify – Governmental Statements and Actions

- What Do Young People Say About Their Relationship with Technology?

- A Somewhat Balanced Article at the Daily Pest?

- Dr. Benjamin Carson – Two Inspiring Videos About our Next President?

- Red Lines, Syria and Incompetence

- The Good Guys are Losing. Why?

- Freedom Can Be Taken. When Inherited or Otherwise Given, Does It Last?

- How Do We Humans Ever Make Good Decisions?

- Libruls and Progressives vs. Liberals

- Boston Bombing Suspects: Grassroots Militants from Chechnya

- China and North Korea: A Tangled Partnership

- What Me Worry?: Why Worrying Does More Harm Than Good

- Happy Birthday, Kim Il-sung

Categories

Archives

Meta

Blogroll

- BLACKFIVE

- Booman Tribune

- Clarissa's Blog

- Crooked Timber

- Crooks and Liars

- Crossroads Arabia

- Daily Kos

- Dan Miller's Blog

- Democratic Underground

- Dr. Jim Taylor's Blog

- EarthAirWater

- Global Voices Online

- Henry David Thoreau’s Blog

- Hot Air

- Instapundit

- Iowahawk

- Jack Jacobs

- Jan Barry

- Little Green Footballs

- Michelle Malkin

- Newsvine Politics

- Outside the Beltway

- Pajamas Media

- Patterico’s Pontifications

- Powerline

- Talking Points Memo

- The Becker-Posner Blog

- The Huffington Post Politics

- The Long War Journal

- The Moderate Voice

- The Sandbox

- The UN Post

- The Volokh Conspiracy

- Today in Afghanistan

- TVNewser

- Watching America

- White House Blog

- Wind Rose Hotel

- Wizbang

- Wonkette

;

;

Dan, thanks for an interesting three articles on the Constitution.

I agree with you on many things, but I think your sense of the future is a bit too gloomy. As constitutional history shows, the pendulum swings both ways, and it will inevitably swing back toward conservative positions.

It seems that views on the Constitution have become as polarized as everything else political. One must believe that either the Constitution is a “living document” or a set of ironclad principles that mean today just what they meant over two centuries ago. As is so often true of extremes, neither is true. Examples abound, and they all reflect the reality that a document written so long ago can’t possibly account for the vast number of technological, economic, political, and social changes that have since occurred. There has to be, and in reality there is, sufficient room to interpret original intent in terms of present reality.

On the Second Amendment in particular (with or without the disputed second comma), it’s clear that the framers intended the populace to be armed (essentially with muskets) and available to be called to duty as a militia should the need arise. They intended to have no standing army, and in their time the call-up of a militia force was the norm. They didn’t appear to have in mind such weapons-related activities as hunting and self-defense; to them, those activities were so normal and expected that they needed no comment. The realities the framers dealt with bear no resemblance to the realities of today.

It’s true that the framers intended their “well regulated” militias to be a deterrent to government tyranny, and you (and others) imply that one of the reasons people must be permitted to “keep and bear” arms is to be prepared to wage war against their government. That’s a silly notion, and I’m always surprised to see it advanced, especially by people who have an understanding of the modern military (as you certainly do).

One last thought about the Second Amendment and gun control: It’s long established in constitutional law that myriad restrictions and prohibitions can be placed on the right to keep and bear arms. As just a few state and federal examples, the law prohibits all but a few people from having automatic weapons of any kind; various types of ammunition are outlawed; the barrel lengths of shotguns and certain other weapons are regulated by law; magazine capacity can be regulated; where, when, how, and if a weapon can be carried is specified by law; so-called assault weapons can be regulated or banned; how weapons are stored and safed within one’s home can be regulated (within limits); and training and licensing requirements regarding firearms are established. The list goes on and on — the law prohibits citizens from having mortars, AA rockets, artillery, tanks, grenades, mines, etc. So the question is not if firearms can be regulated and/or banned by law, but which ones are to be regulated and/or banned. Heller changed very little of this, beyond granting judicial recognition of the right to have firearms for home defense and establishing that some controls may be deemed excessive.

Tom, you say

When the First Amendment was written and adopted, television, radio, telephones, high speed printing presses, Xerox machines, internet or many other marvels of modern technology did not exist. It has not been seriously contended either they were contemplated then or that the rights of free speech and press exclude their use. The principles of free press and freedom of speech were stated in the First Amendment and still apply. To adopt different principles, the Constitution would have to be amended via the procedures set forth in Article V.

True, one can neither construct nor operate radio or television transmitters without appropriate licenses granted by the Federal Communications Commission. Those and similar restrictions on radio frequency emissions are necessary to prevent radio frequency interference: output power, antenna height and other characteristics, hours of operation (in the case of some AM stations) etc are regulated. Without such regulations it would be difficult if not impossible for most radio or television stations to operate. Their purpose is to maximize usage and hence to enhance, not limit, speech and press freedoms.

The Second Amendment speaks of the rights of the people “to keep and bear Arms.” Like the First Amendment, it does not specify the nature of those arms other than that it be possible to bear them, presumably by one person. Mr. Justice Scalia spoke to that in the Heller case majority opinion referred to in Part I. I read it to exclude other weapons such as cannon, various other crew served weapons and the like. The Court also rejected the notions that only weapons in use at the time of adoption of the Second Amendment fall under its protection and that the right to bear arms relates only to militia usage.

I view that as a last resort, to be used only if all other means fail and our constitutional protections turn out to be no more than the porous “parchment barrier” referenced in Part III. What happens then? As a military man with long and honorable service, do you think the U.S. military would turn against poorly armed civilians who, as a last resort, seek to defend their constitutional rights by the only means remaining to them? If the military did so, the civilians might well lose. However, poorly educated savages in the Middle East have not consistently lost to U.S. armed power; they have used such weapons as they have been able to get as well as guerrilla tactics. A scraggly bunch of poorly paid, equipped and provisioned soldiers in our revolutionary forces also used guerrilla tactics. Yet they managed to beat the finely honed British forces.

As noted above, the rights of free speech and press guaranteed by the First Amendment are not so constrained. Civilians probably do not need automatic weapons or high capacity ammunition clips. But do those who wish to exercise their rights guaranteed by the First Amendment need high capacity paper magazines for their high speed Xerox machines, high capacity internet connections and the like? It is not necessary to show any need for such things to get licenses to use them and, indeed, no licenses are required.

In an address which the Honorable I.M Totus reliably informed me that President Obama intended to deliver on gun rights, it was to be said

I do wonder about that, and it makes some sense. Perhaps we have become too accepting of the notion that some rights guaranteed by the Bill of Rights are available only to those granted governmental licenses. If that’s the case, why not all such rights? To quote out of context our gracious Secretary of State, “what difference does it make?”

Part of your argument depends on what the meaning of principles is, to paraphrase our zipper-challenged former president. As a matter of principle, we have certain pre-existing rights, most clearly to life, liberty, and property. We also have rights to free speech, to keep and bear arms (as recognized by Heller), to observe religious beliefs, etc. However, it is clearly established as constitutional to execute our own citizens, to force them to serve in the military, to seize their property under eminent domain, to prohibit them from yelling “fire” in a crowded theater, to prohibit them from keeping and bearing a long list of firearms, to prohibit them from observing certain religious beliefs at certain times and places, etc. The principles as understood and applied over two centuries are, appropriately, understood and applied differently today. I won’t get into the argument about whether the Constitution is a “living document,” but it, like the language it’s written in, has evolved over time and will continue to evolve.

As far as government licensing is concerned, Mr. Totus is mistaken. It is long-established as constitutional (and logical) for the government to exercise the power of licensing to control both priviliges and rights. The government can and does license or otherwise require its prior consent to vote through voter registration and presentation of voter registration cards and/or ID (in some jurisdictions); to obtain a permit (read license) to hold meetings and gatherings in order to exercise speech; to have a license and/or a background check and to be mentally sound and not a felon to purchase permitted firearms, to include a separate license to carry them under certain conditions; etc. The list of constitutionally accepted licensing of and permitting the exercise of rights is very long indeed.

Liberals and conservatives alike accept all this to varying degrees (often depending in large measure on the degree to which they approve of some specific government action or judicial decision). It’s the purist libertarian who has a big problem — in order for him to achieve the kind of government and society he fervently wishes for, it would be necessary to return, if not to a state of nature, then at least to the state of things as they existed in the late Eighteenth Century. That’s neither possible nor desirable, and those of a strong libertarian bent would save themselves a lot of angst if they could understand and accept that reality.

Tom, you say,

I see no need to return either to a “state of nature” or to the late Eighteenth Century. Modern dentistry, the internet and many other aspects of the present are just fine. We should be able to adhere to the Constitution as written, or to amend it pursuant to Article V should enough of us desire that, without doing either. If not enough of us desire it, it should be not be deemed a legislative, executive or judicial function to do it

forto us.The people who wrote and approved the Declaration of Independence, those who fought and died for independence and those who wrote and later adopted the Bill of Rights as part of our Constitution could also have saved themselves a “lot of angst” in ways similar to what you appear to suggest. However, review of our history and that of many other nations fails to recommend salvation of that sort very highly.

Frankly, I’m not so sure about modern dentistry. In the old days when you took your throbbing toothache to your local unlicensed, uncontrolled, untrained barber you could at least have your six-shooter strapped on. Then if he hurt you, you could shoot the &#%$@%&!